Can I visit the Karen Blixen Museum?

November 19, 2025

What festivals happen in Kenya?

November 19, 2025What’s the History of the Swahili Coast?

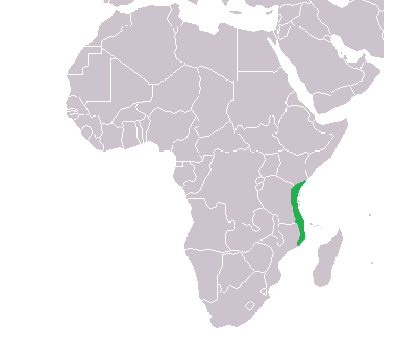

The Swahili Coast stretches along the eastern edge of Africa, a shimmering ribbon of culture, commerce, and history that spans from southern Somalia through Kenya and Tanzania to northern Mozambique. This coastal world is where Africa meets the Indian Ocean, where monsoon winds carried traders, scholars, sailors, and adventurers across continents, and where centuries of encounters gave rise to one of Africa’s most distinctive and enduring cultures: the Swahili civilization.

When travelers ask, What’s the history of the Swahili Coast? they are stepping into a world shaped by centuries of trade, migration, intermarriage, diplomacy, and artistic expression. The Swahili Coast is not just a geographical line—it is a cultural universe, a story of connection between Africa, Arabia, Persia, India, and even China. It is a history written in coral-stone towns, carved wooden doors, bustling harbors, ancient mosques, and a lyrical language that remains widely spoken today.

The Origins of the Swahili People

The story of the Swahili Coast begins with the indigenous Bantu-speaking communities who inhabited the East African coast more than two millennia ago. These early residents were skilled fishermen, farmers, and sailors who understood the rhythms of the ocean and the opportunities it presented. Over centuries, they developed sophisticated maritime skills, giving rise to coastal villages that thrived on fishing, agriculture, and small-scale trade.

By the first millennium CE, these Bantu communities began encountering traders from Arabia and Persia, who were drawn to the coast by the monsoon winds. These seasonal winds allowed sailors to cross the Indian Ocean predictably each year. The interactions that followed—marriages, trade relations, religious exchanges, and cultural blending—laid the foundation for what would become the Swahili society.

Rather than being a culture imposed from outside, the Swahili identity emerged through a long process of integration: African in its roots, yet enriched by influences from across the seas.

The Rise of Swahili City-States

Between the 10th and 15th centuries, the Swahili Coast blossomed into a network of prosperous city-states. These were not united under a single empire but operated autonomously, each ruled by local elites who maintained diplomatic and commercial ties with the wider Indian Ocean world.

Some of the most famous city-states included Kilwa, Mombasa, Malindi, Lamu, Zanzibar, Pate, Sofala, and Mogadishu. These towns were thriving hubs of trade, art, scholarship, and architecture. Built primarily from coral stone, their houses, mosques, and palaces reflected both African craftsmanship and influences from Arabia and Persia.

The wealth of these city-states came from their strategic position along crucial maritime trade routes. Gold from the interior of Africa, ivory, spices, timber, animal hides, and enslaved people were exchanged for Persian ceramics, Indian cloth, Arabian glassware, and Chinese porcelain. The archaeological remains found in sites like Kilwa Kisiwani and Gede Ruins reveal the global reach of Swahili trade networks.

Swahili Culture and Language

One of the most enduring legacies of the Swahili Coast is its language—Kiswahili. A Bantu language enriched with vocabulary from Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, and later English, Kiswahili became the lingua franca of the entire East African coastline. Today, it is spoken by more than 200 million people and serves as a unifying language in Kenya, Tanzania, and parts of Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Swahili culture is characterized by its elegant poetry, refined architecture, intricate woodcarving, music traditions like taarab, and its sophisticated etiquette and social structure. The Swahili people embraced Islam early in their history, and the religion played a central role in shaping their educational systems, governance, and artistic expressions.

The beauty of Swahili culture lies in its fusion—African at its core, yet open to the world, constantly evolving through global connections.

The Arrival of the Portuguese

In the late 15th century, the peaceful ebb and flow of Indian Ocean trade was disrupted by the arrival of the Portuguese, led by explorers like Vasco da Gama. Seeking control over the lucrative trade routes, the Portuguese imposed military and economic dominance over many Swahili towns.

This period brought conflict, resistance, and significant upheaval. Some city-states, like Malindi, cooperated with the Portuguese to strengthen their position, while others, like Mombasa, experienced destructive attacks and invasions.

The Portuguese built forts—including the iconic Fort Jesus in Mombasa—in their bid to control the region. Though their influence reshaped parts of the coastal economy and architecture, the Swahili people maintained a resilient identity, continuing to practice their culture and religion despite foreign control.

Omani Influence and the Golden Age of Zanzibar

By the late 17th century, the Omani Arabs expelled the Portuguese from much of the Swahili Coast, ushering in a new era of prosperity. Under Omani rule, the coastal towns regained their commercial strength and enjoyed increased stability.

Zanzibar emerged as the crown jewel of the Omani Sultanate. In the 19th century, it became one of the most important trade centers in the world—particularly in cloves, ivory, and the East African slave trade. Stone Town’s iconic architecture, with its carved wooden doors, narrow alleys, and coral stone buildings, reflects this era’s cultural and economic vibrancy.

The Omani era cemented Islam’s deep roots along the Swahili Coast and expanded connections with Arabia, India, and beyond.

The Colonial Era

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European powers—primarily Britain and Germany—established colonial rule over the East African coast. This period brought administrative restructuring, economic exploitation, and new infrastructure, including railways linking the coast to the African interior.

Colonialism introduced significant changes to Swahili society, including the redistribution of land, shifts in political authority, and the development of plantation economies. Yet despite these transformations, Swahili culture continued to thrive, adapting to new realities while preserving its artistic, linguistic, and religious heritage.

Modern Swahili Identity

Today, the Swahili Coast remains a region of immense cultural vitality. Cities like Mombasa, Lamu, and Zanzibar continue to celebrate their heritage through festivals, crafts, cuisine, and architecture.

The Swahili language has grown into one of the most important languages in Africa, promoted as a symbol of unity and cultural pride. Traditional Swahili practices, such as dhow sailing, henna art, intricate wooden carving, and poetry recitation, remain alive even as modern influences blend seamlessly into everyday life.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as Lamu Old Town, Zanzibar’s Stone Town, and the Ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani stand as monuments to the region’s remarkable past.

The Enduring Legacy of the Swahili Coast

The history of the Swahili Coast is a story of connection—between continents, cultures, and centuries. It is a history shaped by Africans who embraced the world beyond the ocean yet remained rooted in their identity. It is a legacy of resilience, creativity, and openness.

When travelers walk through the ancient alleys of Lamu, touch the weathered stones of Gede Ruins, sail on a traditional dhow in Zanzibar, or listen to taarab music drifting across the shore, they are experiencing the echoes of a civilization that continues to shape the heart of East Africa.

What’s the History of the Swahili Coast?

It is a story that spans more than a thousand years—beginning with Bantu roots, flourishing through trade, enriched by cultural exchange, challenged by foreign powers, and preserved through modern pride. The Swahili Coast offers an unforgettable tapestry of history, artistry, and connection that continues to enchant travelers from around the world.

To explore the Swahili Coast with expert guidance and immersive cultural experiences, consider booking your journey with Experiya Tour Company. Their deep regional knowledge ensures you experience the beauty, history, and charm of East Africa’s coast in comfort and confidence.